The SEC had a busy December, meeting with all potential issuers of actively subscribed spot Bitcoin ETFs. This meeting has led issuers to universally adopt cash generation methodologies instead of the “in-kind” transfers common in other ETFs. There has been a lot of talk about this change, from the absurd to the serious. However, the TLDR has minimal overall impact for investors, is relatively meaningful for issuers, and reflects poorly on the SEC as a whole.

To provide context, it is important to explain the basic structure of an exchange traded fund. ETF issuers work with a group of Authorized Participants (APs), all of whom have the ability to exchange a predefined amount of fund assets (stocks, bonds, commodities, etc.), a defined amount of cash, or a combination of the two. You can receive a fixed amount of ETF shares for a predetermined fee. In this case, if “in-kind” issuance were permitted, a fairly typical creation unit would be 100 Bitcoin exchanged for 100,000 ETF shares. However, for cash generation, the issuer must post cash amounts in real time based on Bitcoin price changes (in this example, winning 100 Bitcoins). (It must also post the cash amount available to redeem 100,000 ETF shares in real time.) The issuer is then responsible for purchasing 100 Bitcoins for the fund to comply with its commitments or selling 100 Bitcoins if: Restriction.

This mechanism applies to all Exchange Traded Funds and, as you can see, means that cash creation disproves the claim that the funds are not 100% backed by Bitcoin holdings. There may be a very short delay if the issuer has not yet purchased the Bitcoin it needs to acquire after creation, but the longer the delay, the more risk the issuer takes. If it is required to pay more than the quoted price, the Fund will have a negative cash balance, which will reduce the Fund’s net asset value. This will, of course, impact performance and, given how many issuers are competing, is likely to be detrimental to the issuer’s ability to grow its assets. On the other hand, if the issuer can purchase Bitcoin for less than the cash AP has deposited, the fund will have a positive cash balance, which can improve fund performance.

Therefore, we can assume that issuers will have an incentive to offer a cash price that is much higher than the actual trading price of Bitcoin (and for the same reason, a lower redemption price). The problem is that the wider the spread between the generated and redeemed cash amounts, the wider the spread APs are likely to quote in the markets where they buy and sell the ETF shares themselves. While most ETFs trade at very tight spreads, this mechanism could mean that some Bitcoin ETF issues have wider spreads than other ETFs and have wider spreads overall than their “spot” counterparts.

Issuers must therefore balance the goal of quoting a tight spread between issued and redeemed cash amounts with the ability to trade above the quoted amount. But achieving this requires access to sophisticated technology. As an example of why this is true, consider the difference between quoting 100 bitcoins based on Coinbase’s liquidity compared to a strategy using the four US regulated exchanges (Coinbase, Kraken, Bitstamp, and Paxos). In this example, we used the CoinRoutes cost calculator (available in the API), which shows trading costs for a single exchange or a group of custom exchanges based on the entire order book data held in memory.

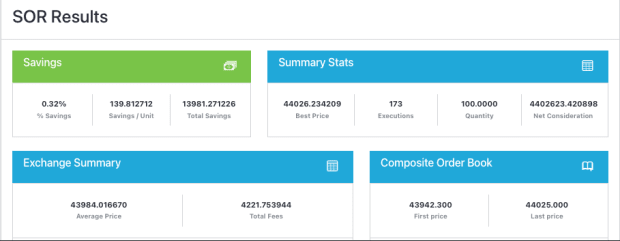

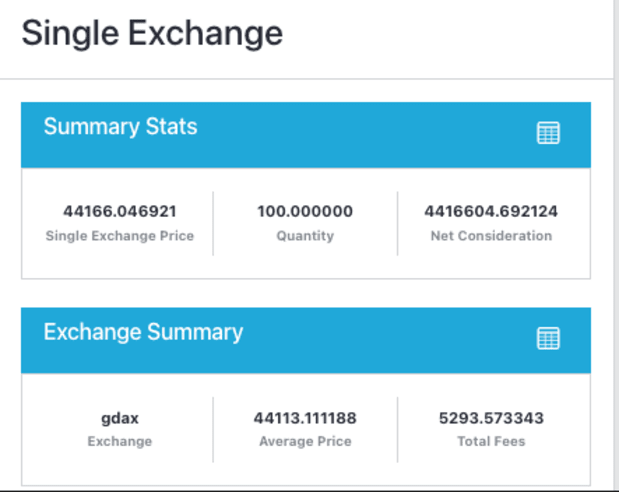

In this example, we see that the total purchase price from Coinbase alone would have been $4,416,604.69, but the purchase price across the four exchanges was $4,402,623.42, which is $13,981.27 more expensive. This equates to costing 0.32% more to purchase the same 100,000 shares in this example. This example also illustrates the technical hurdles faced by issuers, as the calculations must traverse 206 individual market/price level combinations. Most traditional financial systems don’t need to look beyond a few price levels because Bitcoin’s fragmentation is much greater.

Although it is unlikely that a major issuer will choose to trade on a single exchange, it is likely that some will do so or choose to trade over-the-counter with market makers who charge additional spreads. Some choose algorithmic trading providers like CoinRoutes or its competitors, which allow them to trade at lower prices than the average quoted spread. Whatever they choose, we don’t expect all issuers to do the same. This means there can be potentially significant differences in pricing and costs between issuers.

Those who utilize good trading skills can deliver tighter spreads and superior performance.

So, given all these hardships that will be borne by issuers, why has the SEC effectively mandated the use of cash generation/repurchase? Unfortunately, the answer is simple. AP is a broker-dealer whose rules are regulated by SROs such as the SEC and FINRA. However, so far the SEC has not authorized regulated broker-dealers to directly trade spot Bitcoin, which they would have had to do if the process had been “spot.” This reasoning is a much simpler explanation than the various conspiracy theories I’ve heard that aren’t worth repeating.

In conclusion, a spot ETF would be a huge step forward for the Bitcoin industry, but the devil is in the details. Investors should examine the mechanisms through which each issuer cites its issuance and redemption processes and choose to trade to predict which issuers will perform best. While there are other concerns including storage procedures and fees, ignoring a trading plan can be a costly decision.

This is a guest post by David Weisberger. The opinions expressed are solely personal and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.